5. Latin America

The Hopeful Continent

Please leave your comments below. My primary goals in this blog are to elicit feedback and make friends who share this interest.

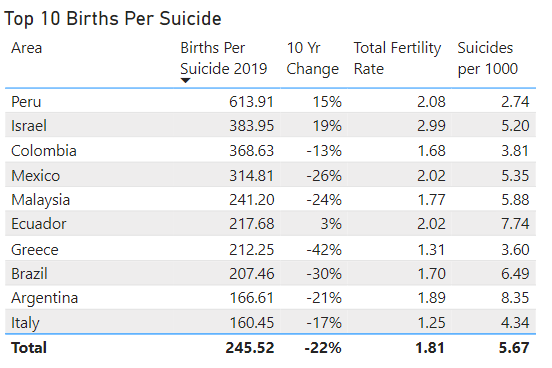

This is the last post about the top 10 most hopeful (defined as births/suicide) countries in our sample. This post will be about how seven of the top 10 are from Latin America, and how five of those are now declining in hopefulness.

Being a data person, my first inclination when seeing this kind of over-representation from Latin America was skepticism. Perhaps Latin American countries under-report suicides (like Muslim countries are known to do). Or perhaps their infant mortality rates are still too high to show the modern pattern. Let’s explore these possibilities.

Scepticism

First I pulled together a variety of stats about the Latin countries and Non-Latin countries shown above from the top 10, as well as the Latin countries not in the top 10, and color coded them.

First of all, suicides don’t stand out in this visual. The suicide rates of the Latin countries from the top 10 don’t seem much different from the non-Latin countries, though they are mostly lower than the rates for Latin countries outside the top 10. I don’t see evidence that their suicide rates are systematically out of whack, although there could be some effect of under-reporting.

Second, however, infant mortality does stand out. See all the red in the top table. The Latin countries in the top 10 do have higher infant mortality rates than most of the non-Latin countries in the top 10, and higher than Latin countries from outside the top 10.

Looking at suicides in more detail, here are all the non-excluded (see original post for methodology) countries by subregion and suicide rate over time.

Here I don’t see evidence of systematic under-reporting from Latin countries compared to other areas. Western and South-Eastern Asia are well below Central and South America. The shocking story here (to be covered in a later post) is the decline in suicides in Eastern Europe. “Blank” refers in this chart to North America (no sub-region).

Looking at infant mortality and births (see Hans Rosling for why this matters), we see below that Central and South America do appear slightly higher than the rest of the top 10 when it comes to infant mortality, but they’re still in the same order of magnitude and have basically reached the flat part of the curve where countries end up after they’ve achieved sufficient levels of health care and female education.

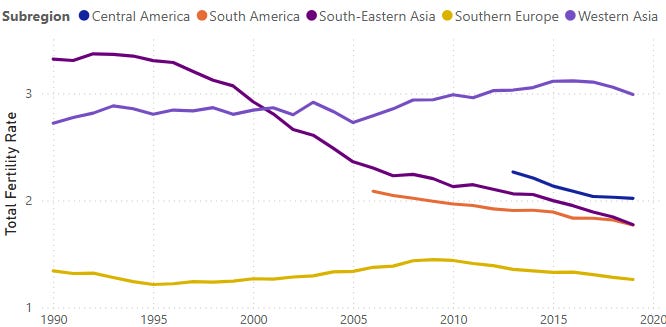

Looking more directly at Total Fertility Rate, we see that the trendlines of Central and South American countries are on the same basic slope as most of the rest of the top 10, further reinforcing the concept that they’re basically modern countries from a birth rates / infant morality point of view.

Thus ends my skepticism. I do not think that Latin American countries are primarily (there could still be some effect) over-represented in the hopefulness metrics because of data issues or an overly-high infant mortality.

They’re Less WEIRD

For those who’ve read Joe Henrich’s The WEIRDest People in the World (highly recommended), you may note that Latin America was neither affected by the middle-ages Catholic Church birth policies nor the East-Asian rice farming culture, the birthplaces of WEIRD psychology.

Because Sub-Saharan Africa and most of the Middle East must be excluded for methodological reasons, that leaves Latin America as our least WEIRD group. This means that, psychologically speaking, they are on average less individualistic and more tribal than most of the rest of our countries.

That’s about all I can say psychologically (hope is basically a psychological phenomenon) as a generalization about the entire continent of Latin America. But it fits with the likely causes of the hopefulness of Peru and Israel, discussed in previous posts.

If there’s a phenomenon (which I think there is, and will eventually describe it) that’s causing a decline in hopefulness in more-individualistic places, then you would expect less-individualistic places to be resistant to it. That’s exactly what I think we’re seeing here.

Latin America may be more hopeful because they’re less WEIRD.

So then Why the Decrease?

If Latin America is less individualistic, and so more hopeful, then what does it mean that their hopefulness is mostly declining?

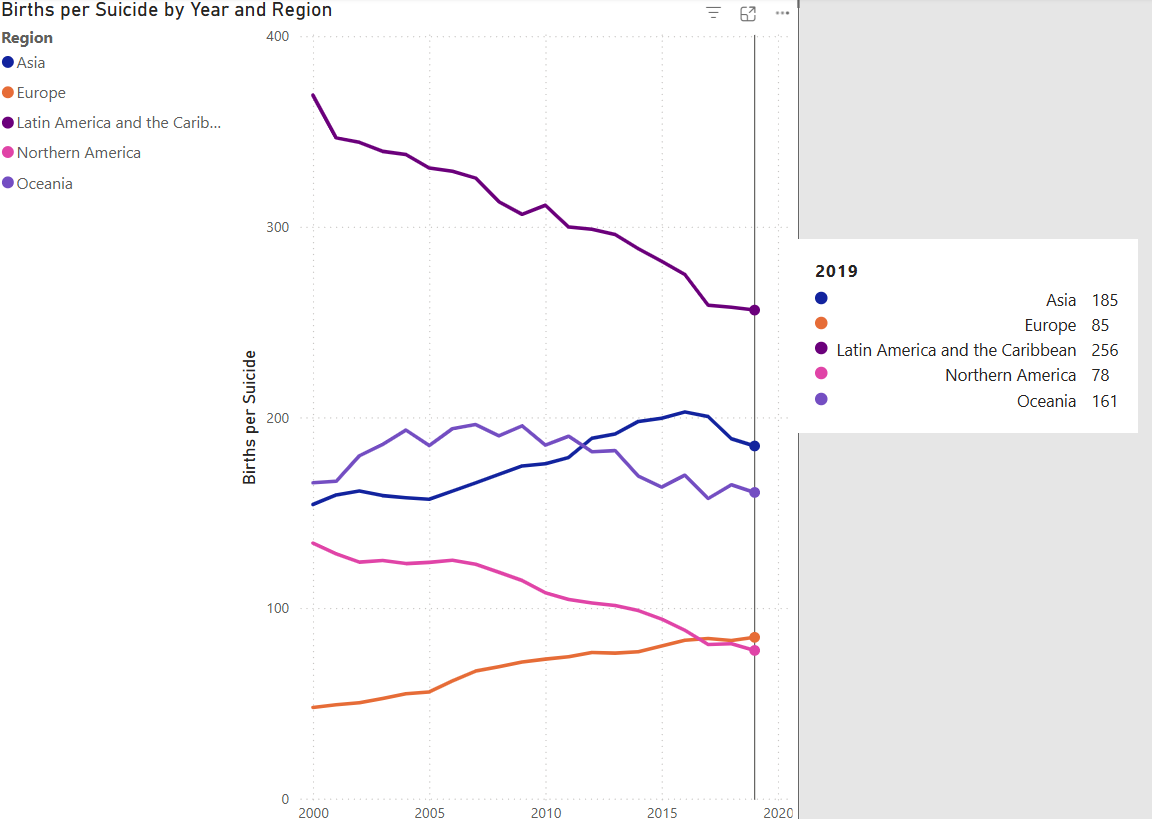

One argument one could make is the psychological adaptation argument, which Jonathan Haidt talked about in The Happiness Hypothesis and many others have discussed elsewhere, which the following chart supports. It’s basically the idea that what goes up (psychologically) must come down, and vice-versa. Europe has the lowest hopefulness and it’s rising, and Latin America has the highest and it’s rapidly falling.

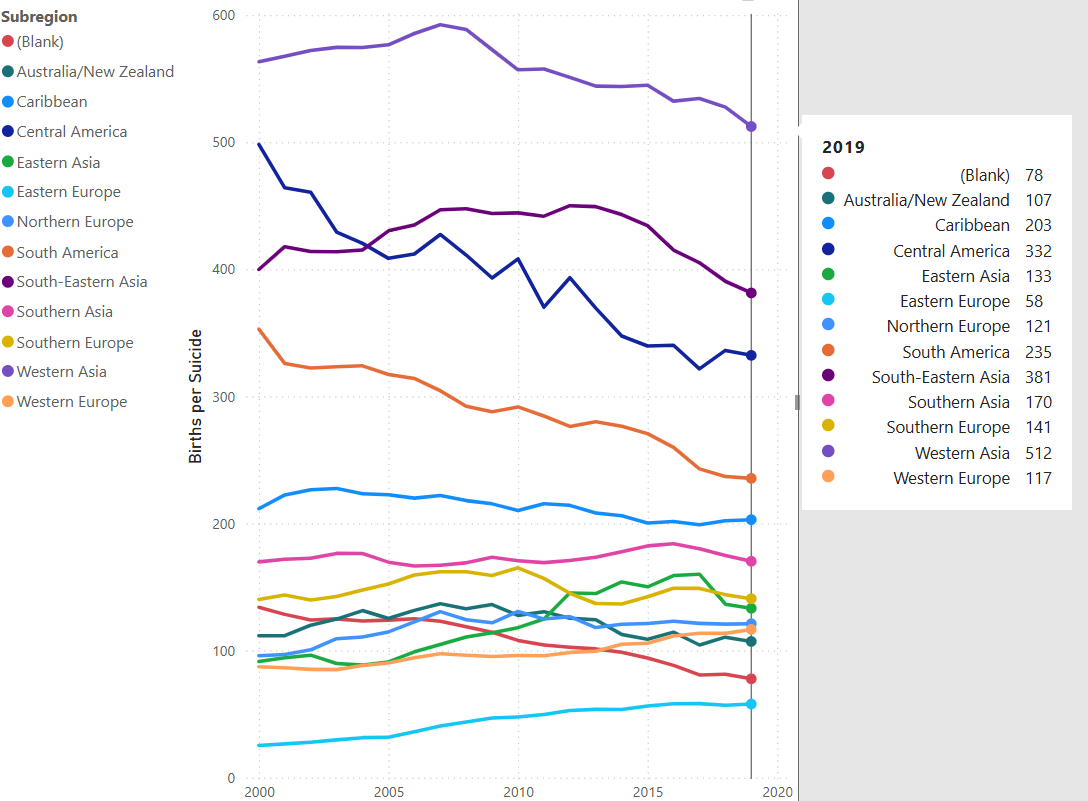

This next chart is similar but with a bit more detail, and shows the same basic pattern except that Eastern Europe takes the low spot and South-Eastern and Western (Israel and Cyprus) Asia show up on top as sub regions.

It sure does seem that there’s some amount of adaptation, with a few exceptions such as North Americans (“blank” in this chart).

There are other explanations that one could make.

Henrich does suggest to a limited extent in WEIRD that Latin America is becoming more individualistic, and one would expect rising social media use to accelerate this. This could partially explain why it’s dropping in hopefulness.

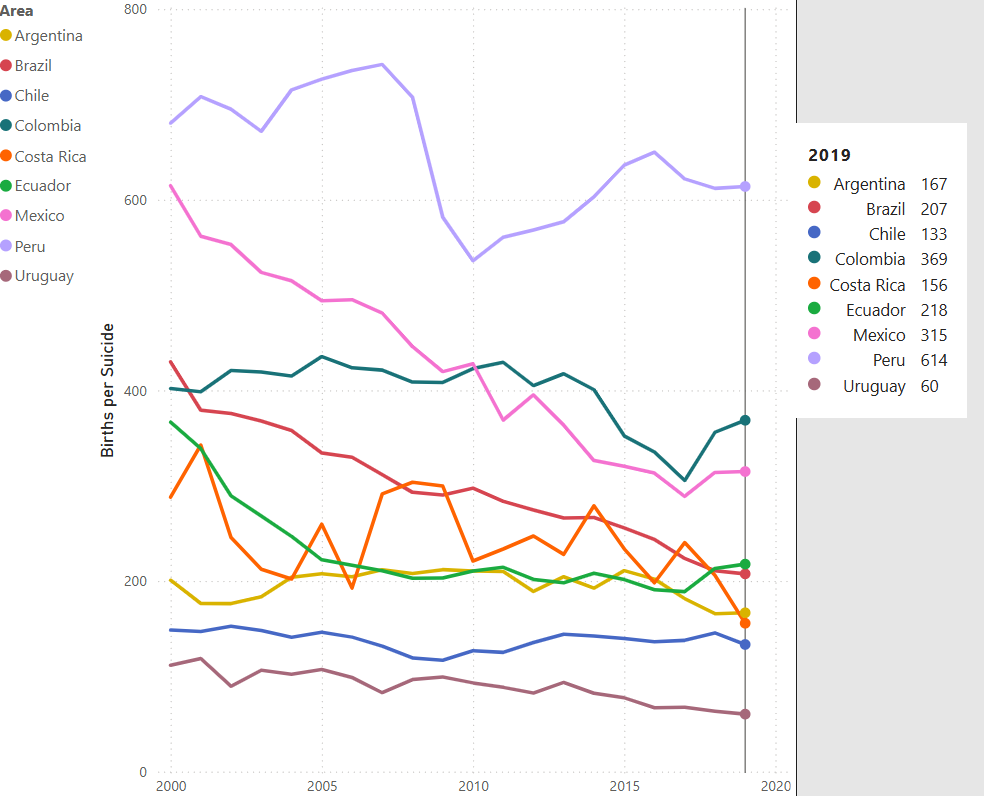

Looking below at individual Latin countries, we see that Mexico, Brazil, and Columbia show the most notable declines in the last decade, while others don’t show obvious patterns. I don’t know of anything which these countries share that the others don’t. If you do I’d love to hear in comments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the high levels of hopefulness shown by Latin American countries are most likely mostly real. However, with the striking exception of Peru and the lesser exception of Ecuador, their hopefulness is declining at a moderate rate.

One potential explanation is that (for better and worse) Latin America has been less individualistic and more tribal than the rest of the modern world, which (as we have seen other places) seems to correlate somewhat with hopefulness.

Their growing individualism could then be a partial explanation for why they may be becoming less hopeful, particularly if someone can explain why Mexico, Columbia, and Brazil are becoming individualistic faster while Peru and Ecuador become individualistic slower. But psychological adaptation (on the national level) could also be an explanation.