9. Eastern Europe

And the Cause of Male Interest in Conspiracy Theories

Please leave your comments below. My primary goals in this blog are to elicit feedback and make friends who share this interest.

Things are looking up!

At least they are for the countries shown below, whose rates of hopefulness are improving.

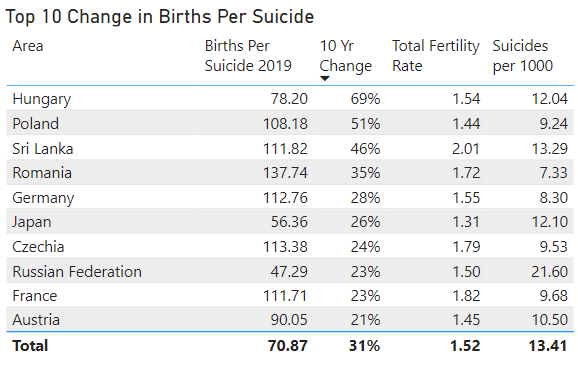

Strikingly, seven of the ten are in Europe, including five in Eastern Europe and both the top #1 and #2. Let’s look at these more closely.

Suicides

As I noted earlier, there’s a “male suicide belt” that stretches from central Europe through Russia to Japan, where male suicides are much higher than the rest of the developed world, and that one factor in this is proximity to Russia.

Is that related to improving hopefulness in Eastern Europe? Let’s see.

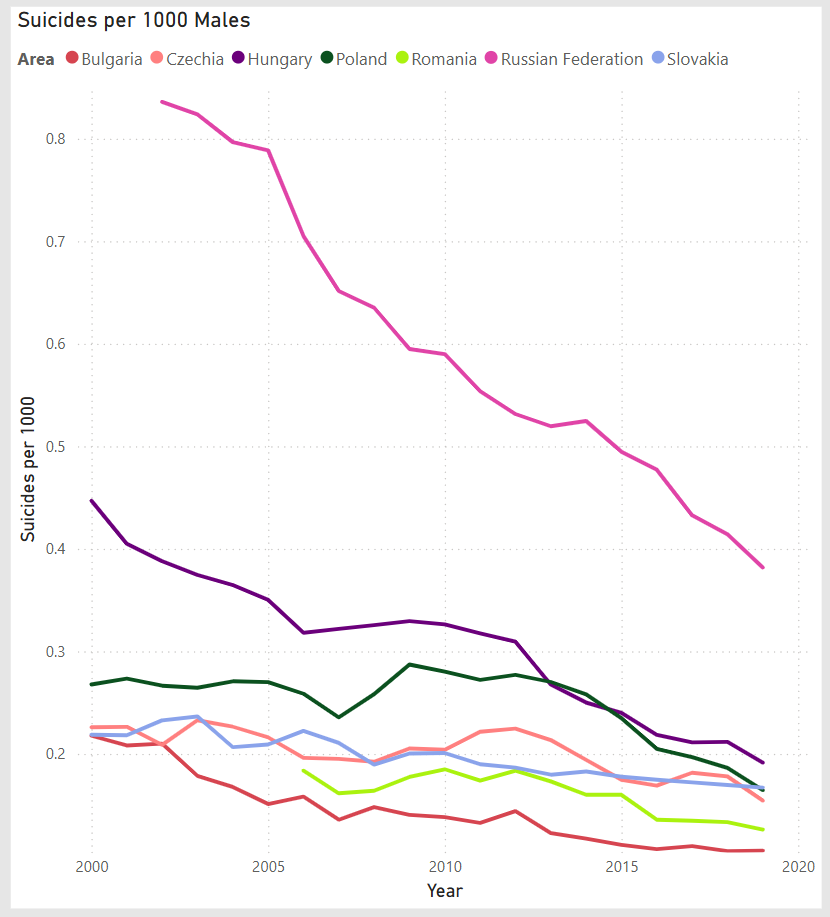

We can see here that male suicide rates in all Eastern European countries have (more-or-less) consistently declined over the past 20 years, resulting in a total decline of about 50% for most countries.

Interestingly, female suicide rates have declined at about the same rate and in the same countries. But this has much less affect on our overall result because female suicide rates in Eastern Europe are a small fraction (10-20%) as high as male rates. In most developed countries, male suicide rates are about double female rates.

I’ll have more to say about this later since it’s the primary contributor to increases in Eastern European hopefulness. But first birth rates.

Birth Rates

The following chart shows change in Total Fertility Rate amongst Eastern European nations since 1990 (or whenever they started tracking this)

Except for Bulgaria, all nations which tracked this pre-2000 had declining birthrates. Then between 2000-2003 they were mostly flat, at which point all the nations started increasing.

The obvious first place to look for the cause of this change is the fall of the Berlin Wall, which signified the end of Soviet Imperialism in Europe. One would not expect an immediate increase in birthrates after this kind of event (“they’re gone, make babies!”), but one would expect the subsequent generation who grew up outside the Soviet shadow to have a different perspective than their parents.

Interestingly, Russia shows the most dramatic change, rising from a TFR of 1.3 in 2005 to 1.8 in 2015 and then dropping again, making them net-negative on birthrate change for the past 10 years. I don’t know the reason for this.

In any case, while increases over the past 10 years on birthrates are significant, as a whole they still only average about 12% across Eastern Europe. So much less significant than male suicide reductions.

Why the Male Suicide Drop?

First, as you can see from this image from maps-russia.com, all of the countries in our top-10 fastest-improving Eastern European countries were part of the Eastern Bloc (Soviet-dominated communist countries) for forty years mid-last-century.

Consider any of the accounts you’ve read of people living in actively-communist countries (as opposed to nominally-but-not-really Communist ones like China) where most aspects of daily life are significantly affected by the government. Those governments are inherently suppressive, as a necessity to prevent some people from rising above others economically.

The theme from those accounts that stands out over and over again is the impersonal nature of the government suppression. People are suppressed by “the system” or “the party” rather than any particular individual. In fact, the bureaucratic nature of those kinds of systems require that one individual can be substituted for another at any time, attempting to ensure that the suppression can never become personal.

It’s hard to exaggerate the extend to which male suicide rates—and still are—were elevated in these countries which fell under Russian or Soviet rule. Despite the rapid (50%) decline over the past 20 years, male suicide rates in these countries are still four times higher than the average for other developed nations, and were eight times higher at the turn of the century.

This makes these countries an astounding outlier!

Because the effect of Russian/Soviet suppression was so much more severe on males, I’ll refer to the force at play here as “Impersonal Emasculation.”

The fact that you even know the word “emasculation,” which has no well-known female counterpart (“efemination?”) is likely because males react much more negatively to their perceived lack of ability to affect the outside world, on average, than females do. Without this ability—especially in a country without a widespread warrior culture as a fallback—it’s hard for many males to form a secure identity.

One theory for why this seems to affect females less is that—when other sources of identity are unavailable—most females can fall back on the always-socially-sanctioned identity of a mother, which offers an inherent ability to affect both the outside world and the future.

One interesting counter-claim is that birthrates were very low in Soviet-influenced countries and increased afterwards. If motherhood serves as an important backup identity for females, one would expect increases in birthrates in communist societies. I don’t know why this doesn’t happen. Perhaps the effect I describe below is a factor for females as well, with the effects felt more strongly in birthrates than suicide rates.

Anyone with a different theory on the role of gender in any of this, please share in comments.

Impersonal Emasculation

If the kind of suppression present in the Soviet-Era Eastern Bloc—which caused males suicide rates to skyrocket—is impersonal, it’s worth looking at the effects of “personal suppression,” or constraints put on the male ability to effect the outside world and the future by someone they have a personal relationship with.

Over the past several decades, it’s become basically indisputable that the two easily-measurable factors which correlate most strongly with self-reported human happiness are marriage and religiosity.

Marriage improves happiness for both males and females, but the effect on males is multiple times higher than for females. Anyone who’s married will readily admin to it introduces dozens (hundreds?) of daily constraints—things you can’t do or have to do—which you could avoid if you weren’t married. And this is in the context of a culture in which marriage is, from a historical perspective, unusually constraining.

As we read in The WEIRDEST People in the World by Joe Heinrich, when the Catholic Church outlawed polygamy in the middle ages, it resulted in arguably the greatest reduction in male violence in world history. Why would an increase in male suppression result in a decrease in male violence? We’ll get to that in a second.

Religion improves happiness roughly equally for males and females, with differences depending on whether you’re talking about “religiosity” vs. “religious membership.” Notably, the benefits of religiosity are more-strongly felt for females, while the benefits of religious membership are more-strongly felt for males. This is notable, because the portion of religion that introduces constraints is membership. So why would an increase in males suppression result in an increase in male happiness?

Conspiracy Theories

My answer to these questions also explains why males are so prone to developing and promoting conspiracy theories.

Unless this is the first website you’ve ever visited—outside perhaps Pinterest—I’m assuming that you’ll readily accept the fact that males are overwhelmingly more likely to promote conspiracy theories, at least online, than females are.

The reason I think this is is that males are respond specifically to the impersonal nature of suppression rather than to the suppression itself.

In my family, I men I grew up with gave me ready access to a wide variety of conspiracy theories from Satanism to the Illuminati, or Obama-birtherism to vaccine-based mind control.

The one thing that all of them had in common was the personalizing of an external constraint:

Satanism: our culture isn’t just sliding into secularism because of impersonal social forces, but because Satan is making it so through specific easily-identifiable products.

Illuminati: the overly-complex and sometimes-seemingly-arbitrary decisions made by politicians aren’t the result of compromise between diverse groups, but are the result of a secret cabal pulling the strings.

Obama-Birtherism: the reason I don’t like Obama isn’t because the large-scale shifting of our culture and ethnic mix makes me uncomfortable; it’s because he’s a liar and a cheater who isn’t an American at all.

Vaccine-Based Mind Control: the reason we have challenging children with ADHD and autism isn’t because of impersonal factors like genetic differences or even the widespread use of poorly-understood toxins, it’s because the deep state cooked up a vaccine to control us.

If males can personalize a source of constraint and suppression, it gives us a sense of understanding about it and an ability to relate to it. We don’t want suppression removed. We just want to have a personal relationship with the one who’s the source of it.

Authoritarianism

The Impersonal Emasculation theory also helps to explain both the rise in megachurches and authoritarian leaders.

With regard to megachurches, Ryan Burge has suggested a similar theory. In a megachurch “We can handle everything at the local level, where we see where the money is going and the leaders are more easily held accountable to the rank and file.” In other words, the “one” constraining your lifestyle is a human you can see and shake hands with rather than an impersonal denomination who is not person-centric but whose leadership rotates periodically. This also explains why megachurches frequently collapse when the founder leaves, and why the sons of founders frequently take the reigns even when they lack the necessary skills: “I know who you are and where you came from.”

To bring this back to Eastern Europe, you may have noted that several of the Eastern European countries—including the top 2—have flirted in recent years with democratic backsliding and authoritarian leaders. One could imagine how a desire to personalize your suppression would make an authoritarian leader appealing to a male who feels that his identity is fading away, and whose only recourse is to try and influence an impersonal democratic system.

Much better to have no influence, but at least to know that your suppression comes from a personal autocratic leader.

This isn’t a very hopeful conclusion if you’re a believer—like me—in democracy. One additional consideration is what I mentioned earlier, that birthrates in Russia are back on the decline, while the rest of Eastern Europe’s are increasing. This may stem from the fact that—in the recent era—Russia has had authoritarian leadership longer than any of the other countries. If so, it may imply that—while males don’t necessarily tire of authoritarian leaders quickly—women get sick of them eventually.

Given the current trends on the world stage, we’ll definitely get a chance to see if that happens in other places and what the implications are.

Conclusion

I see a compelling case that Eastern European increases in hopefulness stem mostly from decreases in male suicide rates. These in turn stem from a transition away from impersonal suppression to personal suppression.

This theory—which I call Impersonal Emasculation—can also help to explain a variety of other mostly-male-driven forces in modern society such as conspiracy theories, the decline in protestant denominations, and the rise in authoritarianism.

It’s like the old agage, “if you’re going to screw me up the ass, at least take me out to dinner first.”

Men really want to be taken out to dinner first.