6: South Korea

The World's Least Hopeful Country

Next we transition to talking about the least hopeful countries (defined as births per suicide) worldwide. First on our list is South Korea (officially, the “Republic of Korea”), a country that’s been the “sad news” a lot recently.

This photo below (and my new email banner image) was taken from a Korean grocery near my house.

Birthrates

Few ARF (America’s Religious Future) readers will find it surprising to learn that South Korea boasts the world’s lowest birthrates, despite spending billions of dollars to reverse that trend.

South Korea has been in the 10 lowest-birthrate countries for decades, but up until the year 2000 they hovered around the middle of that pack. Their remarkable decline follows an odd pattern. First, they dropped from about 1.5 to 1.2 in a single year, then stabilized for the next 14. After that, they dropped down to about 0.8 in a 5-year span and then stabilized again (while not shown in my dataset, their fertility rates have been increasing slightly the past three years).

Shown here with the other bottom-10 East Asian countries, they are the only one to show this pattern. Japan is low but relatively stable. Singapore has dropped in an almost-linear fashion.

I don’t have a good explanation for this odd trend. I don’t know enough about South Korean history to know what might have happened in 2000 and 2015. Economic trends don’t seem to explain it. If you have any ideas, please share in comments.

The standard explanations for the low birthrates of Korea are poor work-life balance and poor gender relations.

On the work-life balance front—and similar to Japan an Singapore—South Korea has been periodically in the news for decades now for their success-oriented culture where parents push kids relentlessly to get good grades and adults work long hours. For example, the South Korean government instituted family day, where the ministry of health turned off the lights and encouraged employees to go home and make babies, but famously many employees continued to work in the dark. They also pay cash to families who have more than two children, and run matchmaking services. But nothing seems to work. Living in the most expensive country on Earth to raise a child, it seems that South Koreans (on average) would rather invest in their careers than in future generations.

The problem is particularly acute around Seoul with its high cost of living, where most of the population live and the total fertility rate is 0.55.

With regard to gender relations, this topic came to my awareness when dating a woman who’d spent several years teaching English in Seoul. She described for me how (in her experience) women are expected to live under the “protection” of a man at all times, either their father or husband. When a woman without a protector is abused (physically or sexually) a common response from the police is to chide them for leaving their father’s house without a husband. The Economist ranks South Korea last amongst OCED countries in their Glass Ceiling Index, indicating that women face much discrimination in the workplace. Perhaps the most practical way in which this plays out is that—in a career-success-oriented culture—many women try to avoid taking maternity leave.

These are compelling explanations, but they come with a caveat. Scandinavian countries famously boast some of the best work-life balance and sexual discrimination numbers, but their birthrate numbers are all below replacement and still falling. Still, South Korea’s birthrates are so low that even Scandinavia’s low birthrate is roughly double South Korea’s.

Suicides

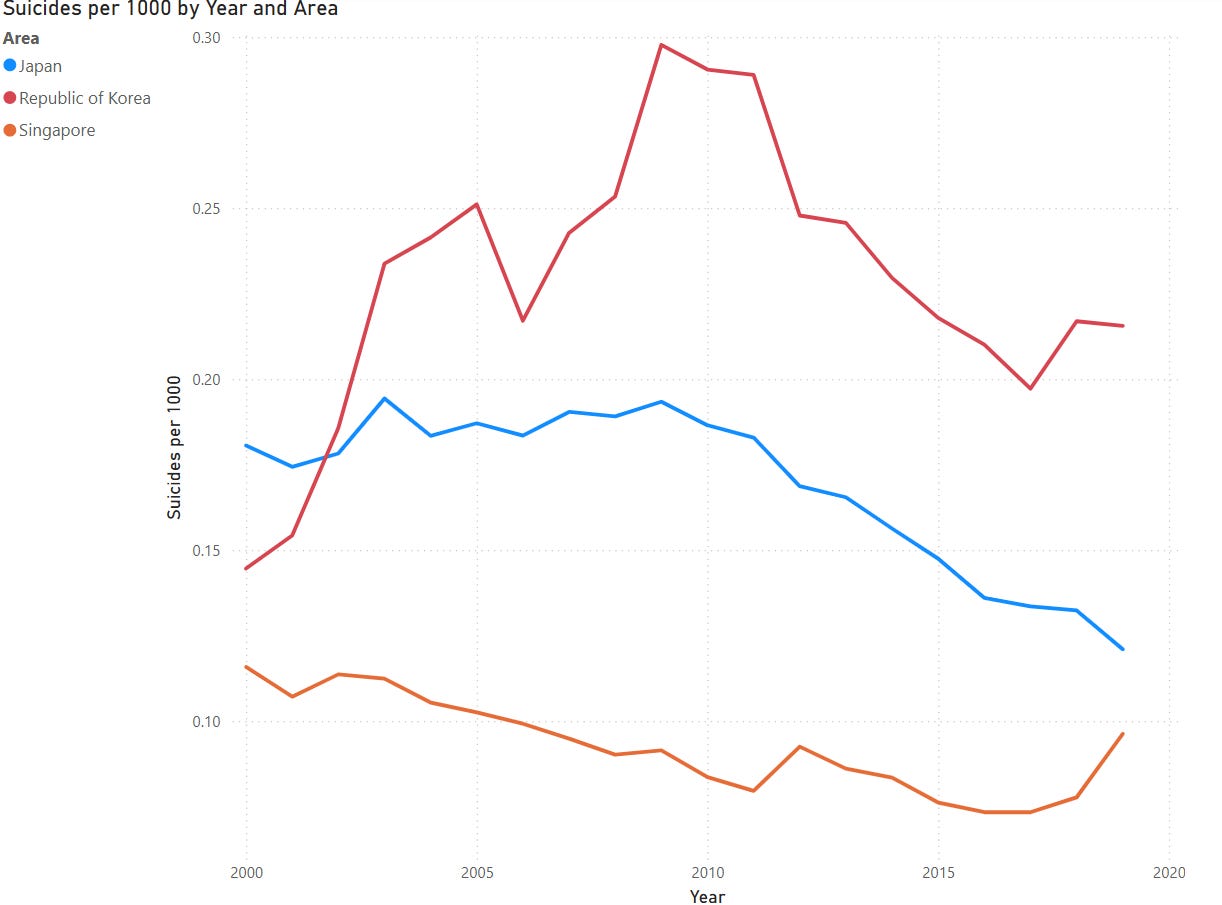

Like birthrates, suicides in South Korea show irregular patterns, with major jumps in 2001 and 2008, and then a major decline from 2011-2017. Again comparing to other bottom-10 East Asian countries, we do not see similar patterns.

One possible explanation for the irregularity of both birthrates and suicides is odd reporting patterns where data for past years is reported late. I have no evidence to support this, though.

The most common explanation for South Korea’s high suicide rate (which is also applied to other East Asian countries) is the same as the first argument above for birthrates: work-life balance.

I first learned about this from my mother, who spent almost 20 years teaching English at various universities in China. She describes how it’s common for college students to take their own lives when they do something that would cause them to “lose face” in the eyes of their family, such as getting pregnant or failing at school. This fits with the East Asian movie stereotypes of Japanese Samurai warriors taking their lives for honor.

The summary on Wikipedia for this topic is excellent, and describes how suicides are the leading cause of death for ages 10-39, as well as for older rural South Koreans. Per the summary, the cause for both groups is the same: a desire not to be a burden to their families if they cannot support themselves economically to the expected standard of living. For older South Koreans, workplace age discrimination is a major factor.

As shown above, South Korea is part of what might be called the world’s “suicide belt” in Northern Asia, stretching from Hungary to Japan.

For my part, I don’t have any good reason to doubt this explanation. I would expect pressure to succeed to correlate with suicide rates at least to some degree.

Alternative Analyses

I did explore several other data sources to try and find correlations with hopefulness. These are as follows:

Screen Time

Hours Worked per Worker

Advertising Spend per GDP

However, after comparing hopefulness with each these metrics I see no meaningful pattern. I suspect that most of the reason is because of inconsistencies in cross-country reporting. That’s the same reason that I abandoned other kinds of hopefulness metrics such as mental health. Inconsistent definitions and reporting are a widespread problem in international reporting, with births and suicides being (mostly) exceptions as simple universally-understood and concepts.

I may someday post more about these analysis, but for now I’ll stop by saying that I couldn’t find anything there.

One other item that I hope to explore further is religiosity. South Korea is notable for Asian countries with its high rate of Christianity (31%), also containing 51% non-religious and 20% Buddhist. I was unable to find any sources breaking up suicide rates by religious identity in South Korea, nor any articles (which would be widely publicized if they existed) that growth in Christianity has helped. Here’s one article which laments the implication that it hasn’t.

Conclusion

Not yet having spent much time exploring the reasons for hopelessness amongst the rest of the bottom-10, my tentative conclusion is that the standard explanation of an emphasis on financial success above all else holds a lot of explanatory power.

Before we firmly conclude anything, let’s explore the rest of our bottom 10.